When I first met Randy, I thought he was crazy.

He was my best friend’s Donna’s cousin. One year, when I was thirteen, Donna’s aunt Deb had agreed to watch me when both my parents had to fly to Poland to a distant uncle’s funeral. I guess he was very close with my mother, exchanging Christmas cards, talking on the phone a few times a year, that sort of thing. They hadn’t seen each other in years, and mom never made it back to the old country until wujek Mateusz passed. Better late than never, I suppose. They didn’t think I should go because at age thirteen a funeral would’ve apparently been too intense for my delicate sensibilities. Now, deep into my forties, I’ve seen my fair share of funerals and I have to say I find the dead and dying beautiful. They’re a half-step removed from heaven, and it shows on their faces.

Randy was obsessed with a dead relative too: his father. He’d been a heavy metal musician who either passed, or left the family and then passed, when Randy was five. Randy was fifteen when I met him, so skinny I thought he was a skeleton with long hair. Acne covered his cheeks to such a degree his rudimentary beard couldn’t cover it. He also had big, black, thick-lensed glasses years before such things were fashionable, which when the light was right made it look like there were blank TV screens where eyes should be. And all he wanted to do was sit in his small room and play his red guitar.

Donna often went to her aunt’s after school because her single dad couldn’t always get out of work soon enough to be home when the bus dropped her off. Luckily, aunt Deb lived only about half a mile away from Donna, on the same bus route. Randy was in high school so he got dropped off sooner. The road was a stretch that connected two major state routes, so it saw a lot of through traffic and not much else. Aunt Deb and Randy, and Donna and her father Cam, each lived in nondescript, multi-family boxes. I don’t know how else to describe them. Donna’s box was divided in half, and aunt Deb’s in thirds. I still remember Randy’s was unit number two, right in the middle, which allowed two sets of neighbors to vent their ire at Randy’s incessant metal riffing. But aunt Deb didn’t mind. She let him play.

Aunt Deb had one of the biggest butts I have ever seen, often stuffed into pink or purple sweat pants which, during that time of year, were stuffed into black winter boots. She usually wore a white zip-up sweatshirt over her ample bosom and massive belly, and glasses just as unfashionable as Randy’s poked through a mass of graying black curls styled in a way that was already a decade out of date even back then. Her teeth were awful—I swear she only had about four remaining up top—and her voice was a nasal honk, but she was clean and friendly and it was clear she loved both Randy and Donna, and her brother too.

Clean was the word for their home as well. Though small and cluttered, it was immaculate. You could’ve eaten off the kitchen floor. Everything was in its place, including aunt Deb’s myriad porcelain dolls and Jesus-themed kitsch; I’ll never forget Our Lord and Savior’s beatific face looking benevolently down at us from a decorative plate hanging on one wall; Ricky later told me he wanted to eat ice cream or something off of it just as a joke, but didn’t want to make his mom upset. She was a good woman, and he was a good kid. Still, all of that distorted guitar I heard from the moment I stepped off of the bus must bothered her a little bit.

“Help yourself to anything in the fridge, honey,” aunt Deb said after hugging Donna and ushering us inside. Though all they had seemed to be off-brand and decidedly unhealthy compared to the stuff my parents kept our refrigerator and pantry stocked with, I did help myself to some purple drink that made me almost gag and a handful of chips so I didn’t make her feel bad. I was going to be spending the bulk of a week there, after all. It was my first foray into the wonderful world of class consciousness, and it wouldn’t be my last.

“Let’s go see my cousin,” said Donna. I knew she had a cousin but she usually just talked about him in eye-rolling terms, like “He smells so bad,” and “All he does is play his stupid guitar,” and “He takes forever in the shower.” But she never said he beat her up or anything, or was cruel, so it was normal kid stuff. I nodded my assent.

On the way to the narrow stairway leading upstairs I passed a picture of what must’ve been aunt Deb with her erstwhile husband, and I have to say she was quite pretty in her younger years. In this photograph, she couldn’t have been more than eighteen, slim and smiling. Daisy Dukes that barely prevented her panties from poking out revealed a pair of unfathomably nice legs that I couldn’t believe were the same ones currently straining the fabric of some heroic fuchsia sweatpants. But it was clearly her. I could see it in the eyes and the smile, complete with a full set of teeth. She and a long-haired, jean-jacket clad man leaned against what I later learned was a 1977 Cobra. I deduced, since the man didn’t look a thing like Donna’s father, that it was her husband. So there had been some happy times. That was good to know. The man wasn’t particularly handsome, but there was something compelling in his eyes and his smile, and it wasn’t until a decade later, looking at that same picture, I figured out what it was: a sense of mission, a sense of seeing, a second-sight, if you want to get all New Age. It was the face of a man who knew and who was driven to tell. But what he knew, that day so long ago, was still a mystery even though I could feel it loud and clear.

The stairwell was paneled in light wood which I knew wasn’t real, scuffed here and there but still shiny. We went upstairs into Randy’s room, which Donna barged into without knocking. It wasn’t like her cousin would’ve heard us over his guitar playing anyway.

The first thing I noticed was the smell, a pungent aroma that screamed “A teenage boy lives here.” I had missed that with my brother, who was already out of his teens and ready to move out by the time I was eight. As he liked to tell me, I was an “oopsie!”

“Come on!” yelled Randy, his current riff ending in a discordant squeal.”

“This is Heather,” said Donna. “She’s gonna stay with us for a few days.”

That got Randy’s attention. He sat up straight and started smoothing out his black t-shirt—if I recall, it was of Pantera—and trying to act nonchalant. I was only thirteen but was already quite pretty, a preppie girl from the good side of the tracks. I got on well with Donna because we had similar sensibilities, even if hers was born of striving to be, whereas I actually was.

“What’s up?” Randy said in a voice already gone deep.

I think I just waved and didn’t say anything. Truth be told, Randy actually was quite handsome under the hair and glasses and acne. Though improbably thin, I could already see what promised to be an attractive musculature. And his features were sharply defined and rather striking, a young girl’s idea of what a grown man looked like. You have to remember that two years makes a huge difference in your teens. You also have to remember that, at that age, girls are smarter and more intuitive. Maybe the smarts evens out in adulthood, but the intuition most definitely does not.

“So why you staying here?” he asked.

“Her parents are in Poland for a funeral,” said Donna, acting as my mouthpiece, my consiglieri. She was always protective of me. “She’s only staying here until my dad gets back. Then we’re sleeping over at my house.”

I don’t know if Randy was disappointed by that, or if Donna expected her cousin to take liberties; I knew what boys and girls did together with the lights out when no one was looking, and I’m sure Randy did too, but I didn’t know if he was that kind of boy, the kind mom warned me about. “Oh. I’m sorry about your loss,” he said. He hefted his guitar. “Do you like music?”

That touched me, both his condolences and his invitation into the world of his passion. “Nobody likes heavy metal,” said Donna, but I told Randy that I did like music. “I play piano and some French horn. And a little guitar,” I lied. My brother played guitar, and he tried showing me a few chords, but aside from occasionally strumming the acoustic he’d left behind when he moved out, I didn’t take to the instrument like I did the piano.

I didn’t tell him that there was something magnetic about guys who played guitar, something I gathered Randy’s mother knew all too well.

His eyes, visible from the shifting light once he moved his head, lit up at my words. “That’s awesome,” he said. “I don’t have a keyboard, but I got an extra guitar.” He gestured to a black guitar case leaning in the corner of his room amidst a pile of tapes, CDs, and music magazines in the process of being organized into some milk crates. “Want to learn? I can teach you.”

“Cut it out, Randy,” Donna said. She put a hand on my shoulder. “Come on, let’s go before he makes you join his band or whatever.”

“I don’t have a band.”

“He’s always trying to get me to play with him but I just don’t like metal.”

“I need a second guitar for the song!” said Randy. “It’s so easy! I don’t know why you’re such a pain in the ass about it!

Donna ticked her finger back and forth. “I’ll tell your mom you swore at me!”

“I want to hear your song,” I said. I plopped myself on Randy’s bed which, I noticed, was made. I looked around his room in earnest. Every inch of drywall was covered in posters of rough-looking, long-haired guys giving the camera looks intended to be intimidating, but which usually looked goofy. I didn’t recognize any of the bands at the time, but one caught my eye that was clearly intended to be humorous of a band mostly in its underwear. I pointed at it. “I like that one.”

“I think Randy does too. A little too much,” said Donna.

Randy ignored his cousin’s barb. “Yeah. That’s Faith No More. Their guitarist is wicked good.” He pointed at a tall man, still fully clothed in jeans and a leather vest over his t-shirt, who had long curly hair, a goatee that almost reached his chest, and was sporting two pairs of sunglasses, one atop the other. “I like their earlier stuff because it’s more metal. He’s not in the band anymore. Their last album’s cool but it’s not the same.” He pointed to a poster next to the underwear guys. It was a black-and-white shot of a long-haired man with a receding hairline singing into a microphone and making the devil sign into the air. “That’s Dio. He’s one of my favorite singers of all time. Sang with Sabbath and Rainbow but’s got his own band too.”

“He’s satanic,” said Donna.

“Shut up,” said Randy. He took a Nerf ball from his desk and whipped it at her. “I told you a million times that’s not a devil sign. It’s the malocchio to keep away the evil eye. He learned it from his Italian grandma.”

“It still sucks.”

“I’m telling my mom you’re swearing.”

“Sucks is not a swear!”

“My mom says it is.”

“Your mom thinks everything is a swear.”

“That’s because she’s actually around, unlike your dad.”

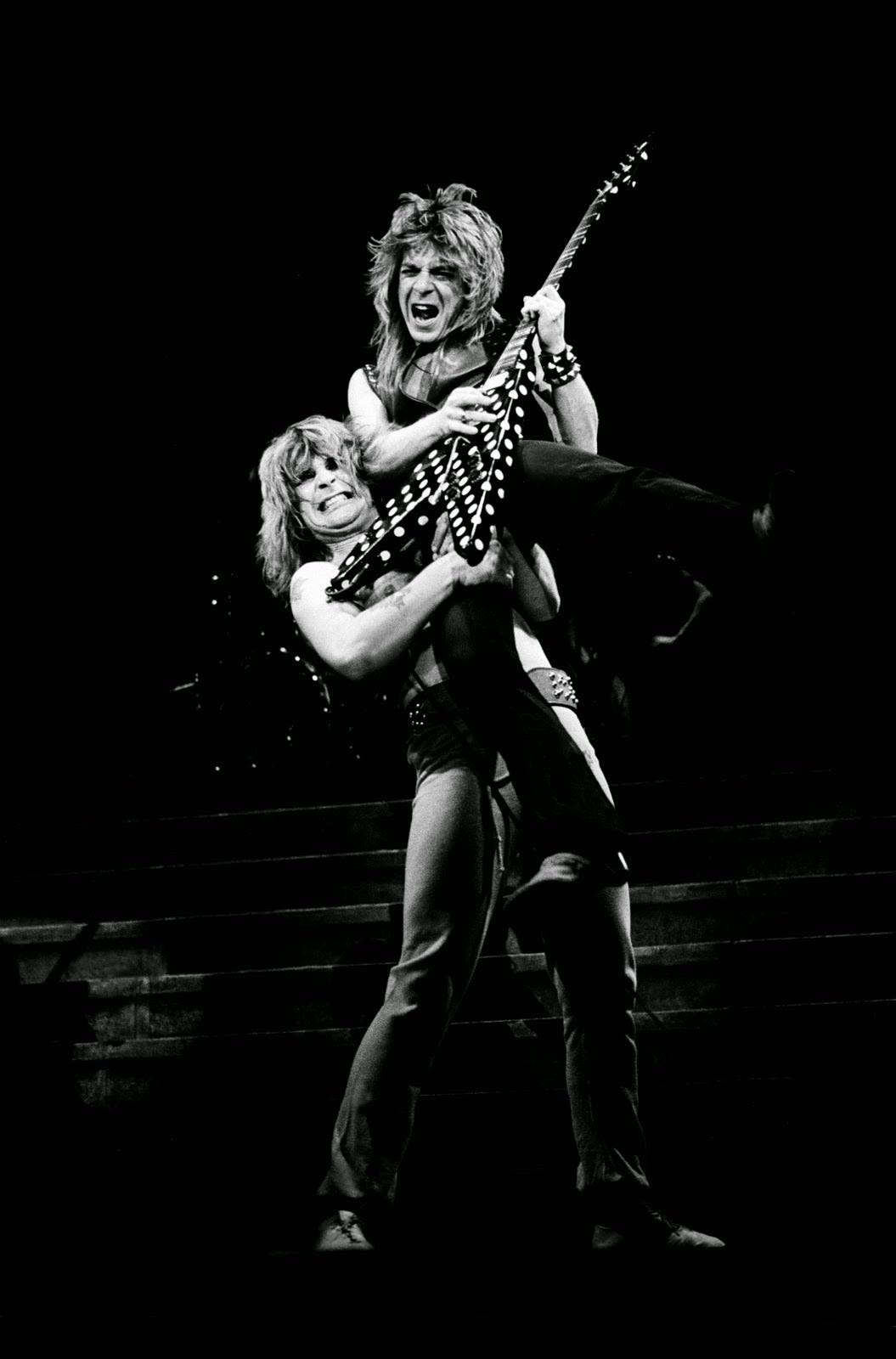

“Whoa,” I said, holding up my hands, not wanting to get involved in this family drama. “Let’s just talk about guitars.” I pointed at particularly striking poster, another black-and-white stage shot. In it, a beefy, guy with long hair (of course), teeth grit in joyous exertion, held up a devilishly handsome young blonde trying desperately to keep playing a polka-dotted guitar shaped like an inverted V. “I like that one.”

Here, Randy’s face lit up like I’d complimented his favorite child. “The guitar or the guy?”

“Both, I guess,” I said. “I like the polka-dots, but the guy is cute too.”

“Oh, God,” said Donna with a giggle. “Here we go.”

“That is my absolute favorite guitar player of all time,” Randy went on. His voice took a reverential cast like he was recounting the past glories of Rome. “Randy Rhoads. Original guitarist for Quiet Riot then played with Ozzy after he left Black Sabbath. Total legend. His technique was just so good. That’s who my dad named me for.”

I shifted my eyes from Randy Collins sitting across from me to Randy Rhoads hanging on the wall. I saw no resemblance except for the long hair. “Why isn’t your guitar pointy like that then?” I said.

Again, Randy gestured to the guitar case in the corner. “Open that up.”

I looked to Donna, as though I needed her permission. “For real?”

“Yeah, for real,” said Randy. He started playing a song I recognized. “You know this one?”

I stood and traversed the few steps to the guitar case in the corner. “I’ve heard it before.”

“‘Crazy Train.’ Everybody knows this riff. And this solo.” And then Randy started tapping on his guitar with both hands, which even I, who did not care for heavy metal at all, had to admit looked as cool as it sounded.

I put the guitar case on the bed. “Is that your favorite solo?” I yelled over the din.

Randy stopped. “Yeah. Well, my favorite solo by someone else. Not my favorite solo of all-time.”

“He never lets me touch this,” Donna muttered as I clicked the case’s latches and opened the top. In it was a guitar much like the one Randy Rhoads played in the picture, but it was gleaming white instead of polka-dotted. “It was Uncle Gary’s.”

My hand stopped halfway to the strings. “Your dad’s guitar?” I asked Randy.

“Uh-huh. It’s okay, you can touch it.”

I strummed an open chord. It didn’t sound like much but goosebumps erupted on my arms nonetheless. “Wow, it’s nice.”

“I’m gonna do that too,” said Donna, strumming the strings a few times, smirking at her cousin all the while. She pulled her hand back, perhaps a little too quickly. “Wow, that does feel nice. I mean sound nice. I mean I don’t know.”

“It’s okay. Dad wanted it to be played.”

“Why don’t you play it, then?” I asked.

Randy hefted his guitar. “This is mine. I bought it with my own money. Anyway, red is my color. White was my dad’s.”

I didn’t know what to say to that, so I let Randy’s words sit and shut the case.

Randy didn’t join us for dinner. After trying his best to give me a crash course in heavy metal—I learned all about the so-called Unholy Trinity” of metal (“Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath, and Deep Purple really laid it all out,”) the New Wave of British Heavy Metal (“Judas Priest is one of the best, but I like Saxon too,”) the Bay Area thrash scene (“Guys like Metallica and Slayer, Anthrax, those guys who put the speed of punk together with metal,”) and some of the newer groups (“Pantera might be the best out right now. There are even some of the, like, wimpier groups like Smashing Pumpkins who can get pretty heavy, but they’re metal. Alice in Chains, though; they’re all right”)—Donna declared she couldn’t take the smell anymore, and hear ears hurt, so we went downstairs to eat something. “That boy always eats late,” said aunt Deb. “But he likes to play that guitar.” At this hour, Randy kept his amp turned down low, but we could still hear him running through scales. I wondered when he got his homework done. Or if he ever did it at all.

We ate mac n’ cheese with hamburger. Aunt Deb assured me it was not from a box, that she made it from scratch, even the cheese sauce. “Everything but the pasta,” she said. And it was tasty. Definitely not what I was used to. I only ate a little bit. As much as I liked aunt Deb, I did not want to be as big as her.

Donna’s dad got there around eight, right as we were finishing out homework at the now-cleared kitchen table. The sounds of Wheel of Fortune coming from the sitting room clashed with Randy’s playing, but it didn’t hurt my ears and was in fact quite homey. Maybe a half-second before Donna’s dad rang the bell, Randy played a figure that made all of my skin tingle and all of the little hairs on my body quiver. Some ascending, vaguely Eastern “do-do-doo-doo-do” I wish I could describe with words. I tapped Donna’s arm. “What was that?”

“The doorbell?”

“No, what Randy played.”

She shrugged. “I wasn’t paying attention.”

“Hey guys, sorry I’m late!” Donna’s dad Cam was a square-jawed, fit man in his mid-forties. His face was weathered and his hair receding and graying, but he still cut an attractive figure, if a short one. He wore jeans and a brown leather jacket over a green sweater. I noticed his shoes were dressier than I expected. I’d thought he was a mechanic at a car dealership, but Donna later told me he’d moved into sales.

Aunt Deb came out of the den. “Took you long enough.” She smiled. “Girls thought you’d abandoned them.”

“I’d never leave you, sis,” said Donna’s dad. Far from an offhand comment, there was a lot of force in it.

“How’s the new job?”

Donna’s dad shrugged. “It’s a lot going on. I’ll tell you next time we do dinner together. Come on, ladies. School comes early.”

I couldn’t get that little riff Randy played out of my head. It buzzed around as I lay next to Donna in her queen-sized bed. I tried to I imagine what notes would come next; I have a pretty good ear for melody, but nothing I could think of worked.

The next day was similar to the last, though Donna’s dad was actually home in time. The next day, too. As much fun as I had with Donna, I wanted to see Randy again. I couldn’t tell Donna, of course. I mean, I didn’t even talk about him to her, even though I had so many questions: Why isn’t he in a band? How does he do in school? Does he ever do his homework? Does he have friends? Does he give guitar lessons? What happened to his dad?

That last question was just rude, at least according to how I was raised. The other questions might make it seem I liked him, which I have to admit I thought maybe I sort of did? He was an interesting boy, that was for sure.

I was getting worried I’d never see him again. It was Friday, and my mom and dad were coming back that Sunday. But then it happened: before getting us ready to get on the bus, Donna’s father told us to go to aunt Deb’s because he’d be working late. I later learned his “working late” meant “going on dates,” but he didn’t have the heart to tell Donna he was out looking for love. Her parents’ divorce had been bitter, and Donna was close with her mother, whom she only saw sporadically due to her, in a reversal of how these things usually play out, having moved to California to start a new life. Still, Cam wisely figured his single life would hurt her too much, and he was right, but his deception hurt even more. But that’s a story for another day.

My ears were still full of that strange riff Randy had played. I went through permutations of it in my head, inversions, chords that might have made an appropriate harmony, but my musical abilities were still in their infancy at age thirteen; I didn’t have the vocabulary or experience to know what I should’ve been doing, or what would’ve worked with that melody. But even if I had, I think what Randy had played defied all conventional musical rules. It defied everything.

The bus ride was torture. It felt like our driver was going fifteen miles per hour the whole way. My leg couldn’t stop shaking, nor my heart stop beating. “What is wrong with you?” Donna said. “You haven’t been listening to me at all.”

“Donna, what happened to your uncle Gary?”

The question took her by surprise. My friend brushed her pretty bangs out of her pretty face and pushed out her lips. “Well, nobody knows, for real,” she said, her voice quiet. I leaned in, as eager to listen as if she were imparting a dying wish. “My aunt Deb says he ran out on her because he cared more about his music than their family.”

“How old was Randy?”

“Five or something. I was real little too. Uncle Gary was in a band that almost made it big.” She told me the name, which I didn’t recognize. “Had a song that some radio stations here played, and I think it started to get played in California!” Her face lit up as she spoke the name of that state, the golden paradise all of us kids in flyover country dream of. “Uncle Gary played guitar and he wrote all the songs.”

“The solo,” I said. “That’s Randy’s favorite solo. The one he wanted to tell me about.”

Donna nodded. “Yeah.”

“So, like, he died on the road? Car accident?”

“Bus accident,” said Donna. “It was horrible. No one knew their driver was drunk. Everyone survived but my uncle.”

“So he never, like, left aunt Deb, right?”

“She says he did. But not for someone else. For the band. For music. She never forgave him. Or music.”

“But she lets Randy play.”

“That’s because it’s all he has of his father.” The bus stopped at aunt Deb’s house. “Don’t you dare tell Randy I told you any of this.”

I gave Donna my word and stepped off the bus. As usual, aunt Deb was waiting for us even though we were old enough to walk the twenty-five feet to their house. And like usual her house was warm and comfy and clean. I grew to enjoy the smell of lemon-scented cleaning product mixed with cooking food, and the comforting sight of her Jesus kitsch, and of course Randy’s constant guitar playing; thirteen-year-old me found the dichotomy between her religion and her tolerance for heavy metal music, even having been married to a metal musician, strange but also charming.

Donna wanted to watch some TV; I think Saved by the Bell or something like that was on, but I asked if I could go say hi to her cousin. “Okay,” Donna said, “but not a word, remember?”

“Got it,” I told her. We even did a pinkie-swear just to be sure.

Randy was very happy to see me. He shot up, I kid you not, before the door was even open, “Hi Heather” out of his mouth before he saw me. Today he wore a black Judas Priest shirt and some fingerless leather gloves. A studded belt circled his skinny waist, and not for the first time I wondered if the boy ever ate.

“Hi Randy,” I said. “What’s up?”

He flipped his hair, trying to appear nonchalant, cool, in that way most teenage boys just couldn’t do. I noticed he had shaved, which did his acne no favors. “Practicing. Wanna hear?”

“Um, hi?” said Donna, offering a little wave. “I’m here too?”

“What’s up, cuz,” Randy said, not taking his eyes off me. He picked up his guitar and, standing now, proceeded to rattle off a flurry of notes. “Working on learning a new solo. ‘Strange Reality’ by Savatage. Really cool one.”

“Yeah,” I said. “But what’s your favorite solo? You never told me. Your song.”

Randy’s eyes lit up behind his massive eyeglasses. “Are you, like, into metal?”

I shrugged. “I don’t know. It’s interesting.”

“What do you listen to now?”

I shrugged again. “I dunno. Like, Madonna. TLC. Mariah Carey.”

“Oh God. Anything with a guitar?”

“Um, No Doubt? Oasis?”

Randy made a face, which I didn’t appreciate. I didn’t make fun of his tastes in music, and I didn’t know why he had to make fun of mine. It was just music. Except it wasn’t. To some people, music was life. And death.

“Don’t be so mean,” said Donna. She gestured around the room. “Not everybody likes crappy stupid heavy metal.”

“Language,” said Randy. “I’m telling.”

“Go ahead, tattletale. I don’t care.”

“Can you play me the solo now?” I offered.

Randy regained his composure. “Yeah, definitely. It’s not my song. It was one of my dad’s. He was a musician too, was in a band. They were awesome.” He cleared his throat like he was about to sing but started playing instead. “Isn’t as good without the full band,” he muttered, but the solo was nice. It began with some twiddly sounding high notes before his fingers started dancing all up and down the neck. It was impressive, but didn’t sound all that great, until he hit that sequence I’d heard a few days before while Donna and I were doing our homework.

“Wait, stop!” I yelled. I actually touched Randy’s picking hand. “That! That part! That’s the one I heard! Play it again!”

Randy did as I asked, and again I felt that chill ripple across the surface of my body.

“Why does it do that?” I asked.

“You feel it,” Randy whispered.

Donna’s head swiveled between us. “What are you talking about? Feel what? Your ears bleed?”

“Hold this,” said Randy. He unslung his guitar and handed it to me. It made a harsh squawk of feedback as my hand wrapped around the neck.

Randy rushed to the corner, where the CDs and magazines were more or less sorted out, opened the case, and took out his dad’s guitar. “Can you play?” he said, jutting his chin at the red guitar in my hands.

“Uh, no . . . maybe?”

“You said you did.”

I scowled at him. “I said a little bit.”

His sheepish actually made me feel bad. “Let me show you. Do you know how to play barre chords?” He had just finished getting another strap onto his father’s guitar.

“Yeah.”

“Good. The rhythm part is easy.” Guitar still unplugged, he strummed it for me. It took me a few go-rounds to get the hang of it but it wasn’t that hard.

“Awesome. Awesome, awesome, awesome,” said Randy. He was shaking so bad Donna and I could see it.

“What’s wrong?” Donna asked. She was honestly concerned. “Are you all right?”

“This is it, oh my God this is it.” He got to one knee and bowed his head as if in prayer and then stood. “This song, my dad’s song, it’s called ‘Song of Life.’ He didn’t finish the whole thing, the real thing. The version his band cut wasn’t finished. I finished it. I have his notes, right here!” He stepped to his desk and flipped a few notebook pages. “I got it right, because I felt it too, but you need two guitars. One to play the rhythm part, and then to play the accompaniment, but the people playing can’t just play it, the have to feel it. That’s what was missing. Do you read music?”

“Yeah,” I said, not really knowing what I was signing up for.

“Shut the door, Donna!” said Randy. “Don’t let my mom in. Not yet. Not until . . .”

Donna did as her cousin asked. “Until what? You’re scaring me, Randy.”

“See, not everyone can feel it,” said Randy. He fumbled with another patch chord, but finally got it plugged into his amp, which had two inputs. “None of my friends. Not even mom. But you . . . I knew you could the second you touched dad’s guitar. All right, keep playing that!”

I did. Playing an electric guitar was a lot easier than trying to hold down the strings on my brother’s acoustic guitar, which sliced through my fingertips like wires. These strings were lighter and almost felt like plastic, though in truth they were usually steel or nickel or a combination of the two.

Randy got into the solo, which sounded so much better played on his father’s guitar. Different. Alive. I felt my soul want to leap out of my body. Even my small rhythmic contribution made Randy’s playing sing. “Heather, your hair,” Donna said. I didn’t know what she meant, but I saw Randy’s hair also standing up as though under the influence of a Van der Graaf generator. When he got to the part I liked, that had really resonated with me, he stopped playing, breathing heavily.

“Oh God, oh God. Now you have to play this part.” Randy took a sheet of music from his desk. “You can read, can’t you?”

“Yeah,” I said. I had to wipe sweat from my brow, which was weird. It felt like I’d been running full-speed. “Randy, what are we doing?”

“Dad knew. Dad knew. He could see into the future, I swear to God. He was a prophet, a genius. He told me before he left he’d never see me again, not until later. That I’d understand later. That he had to go but that I’d never be alone, not ever again.” His face crumpled for a second, and I knew he was fighting tears. “But this song, this is what he left me. It was tucked into my freaking sock drawer before he left on that last tour. Every time I’d hear his song on the radio . . . once I learned how to read music and play guitar . . . it was this but it wasn’t. I read his notes . . .”

“You’re scaring me,” said Donna. “I’m telling your mom.”

“Don’t!” Randy and I both said.

“Donna, let me play this,” I said. Randy was scaring me too, and like I said, I thought he was crazy, but he was also exciting and . . . I don’t know. Driven. “It sounds really cool. And it’s important.”

“Please, cuz,” Randy said. “Please. I promise you this will be worth it. This’ll all be worth it. This is called ‘Song of Life.’ Of life. Think about it.”

Donna stood down. I went over the second part I had to play, a bunch of sustained notes behind Randy’s solo that harmonized perfectly with what he was playing. The guitar felt alive in my hands, a feeling I’d never before experienced with music but would feel again and again later in life.

We were finally ready. Donna slipped out and ran interference when aunt Deb called us down for dinner, telling her we were helping Randy with a project for his school music class. Back in the room, she was just as eager as I was to see just what in the world Randy had promised us.

“Ready?” he asked, smiling.

I liked that smile. In my mind’s eye I could see him without the acne and, a little older and more mature, maybe a little more care given to that hair of his. I smiled back. “Ready.”

We had a few false starts, stopping a little way’s through when one of us messed up a part we had no trouble playing earlier. But we’d never played the solo to the end. This time, though, we could tell right from the very first chord that it was the take.

Everything was electric. I felt the charge in the air. Our hair stood like Donna had pointed out, though hers remained flat on hear head. I could hear nothing, just our song. I saw nothing, just my fingers and Randy’s, occasionally glancing up into his face, grimacing like Randy Rhoads on the poster on his wall. However much I’d love to have hugged him like the big man grabbing him, I knew I had to finish this song first. I knew we were linked. I knew life would never be the same.

I knew music had a power I didn’t think it best to dive all the way into.

We reached the part where I had to play those long tones under Randy’s expert playing. Donna said something; I saw her mouth moving from the corner of my eye, her own eyes wide open; she started clawing at her face. I kid you not, as I sit here today and write these words, the papers on Randy’s desk, his father’s papers, started to twitch, to move, to float. I didn’t think we were playing loud enough for the air molecules to do such a thing, but maybe the contours of our music were shaping those molecules, forcing them to do our bidding.

And then I flubbed a note, and it ended.

“Oh, come on!” said Randy. “Why’d you do that?”

I was taken aback. Randy screamed at me. He didn’t have to do that. I wasn’t used to having older boys yell at me.

“God, don’t be a jerk!” Donna said. “Why are you having a flip-out attack?”

“I’m not, I just . . . I’m sorry. Heather.” He knelt in front of me; I could only see my reflection in his glasses. “Can you play it right?”

“No, I don’t think so. It’s too hard. I told you, I only play a little.”

“But you can read music. And you picked this up wicked fast. And you’re smart and . . . I think you can do it. Can you try again? Please try.”

I looked to Donna then back to Randy, staring up at me. “Okay,” I said.

“Come on, let’s take a break,” said Donna.

“But didn’t you feel it?” I said. “Didn’t you see, you know, stuff move?”

“I did, and I don’t like it.”

Randy stood and held a finger up to his cousin. “One more try, cuz. Please. For me. For dad. For . . .” He looked like he was about to cry.

“One more try, and then I’m all done,” said Donna. She crossed her arms and held her head imperiously high. “I feel wrong. Like we’re messing with stuff we shouldn’t. Like Ouija boards and the other things your mom talks about. I thought they were crazy, but now I dunno.”

“This isn’t like that,” said Randy. “This is rock n’ roll. This is life. ‘Song of Life,’ remember?” He winked at Donna and right then I knew I was going to play the song correctly. I don’t know why, but I wanted to make Randy happy. “You ready, Heather? You’re awesome, you know that?”

“Okay.”

“We should start a band.”

“Let’s just play this,” I told him. He nodded, counted us off, and we got ready for take two.

I got to the part with the long notes again, but through some combination of focus and not thinking about it too hard, I was able to nail each and every downstroke. My contributions to the song melded with Randy’s and as bizarre as it sounds I felt like I was a part of him. It was as intimate as two human beings could be without . . . you know . . . at age thirteen I didn’t have the words, but I had the idea.

And then I heard it. A voice. “Why . . . why?”

It wasn’t me who’d said that. Or Donna. Or Randy. We kept playing even though Donna slipped right off the bed, grabbing her chest and heaving like she was having an asthma attack.

“Why?” that voice groaned again.

“Dad!” Randy shouted, holding the last note. I did the same, letting them ring out, letting the two tones asymptotically draw closer but never touch. “Dad, it’s me! It’s Randy!”

“Randy?” The voice was disoriented, confused. “No, stop, please.”

“Randy!” I yelled, but he didn’t hear me, or didn’t listen. “Randy, stop it!”

Tears streamed down his face. “Dad, oh dad!” Somewhere in the air between him and his desk a small patch of air started to shimmer, to shake, to bend, and I knew if it kept going I’d hyperventilate just like Donna, start frothing at the mouth, and legitimately lose my mind.

That disturbance in the air started to widen. An effulgence of light bled out, so bright it hurt my eyes. “Please stop,” the voice said, the words painted with tears and worry and abject fear.

That was it. The “please” is what touched me. I dampened the string on my guitar and placed my hand over the neck of Randy’s. The music stopped, the voice was gone, and the air was once again normal and undisturbed. We could hear again, the strange overwhelming background roar I hadn’t realized was there quieted with jarring suddenness. Randy cried silent tears, lips blubbering, before whipping off his glasses and turning to me. I thought he was going to hit me, but not Randy. Never Randy. “W-w-w-why?” he managed to get out, before hugging me and burying his face in my shoulder.

I didn’t know what to do. Our guitars clashed together with a horribly violent sound. I gently pushed Randy away and messed with the knobs on my guitar until I found the volume. “Randy, he’d come back again only to die!” I said.

“What the fuck was that?” shouted Donna, her wits returned. “What the fuck?”

“Randy, listen to me! He’d come back and then he’d die again and he’d have to go through all of that! He’s already there!” I waved a hand vaguely that way. “In Heaven or the afterlife or whatever! If you brought him back it’d be like getting taken away from . . . you know . . .”

What was I supposed to say? His parents? God? Did I even believe that? Did Randy? Randy’s mother sure did. Maybe I did too even if I didn’t know it. It was very confusing.

Randy nodded, but otherwise remained semi-catatonic. “We have to get rid of this music, do you understand?” I went on. “You can’t do this again, Randy. This was a mistake. This was . . .”

He slung his dad’s guitar around onto his back, grabbed me and kissed me, very quickly, on the lips, and then held me tight as Donna’s screams continued and then petered out. “Dad knew,” he whispered. “Dad knew. This is why this happened. Dad knew.”

“Dad knew what?” I said when I’d regained my voice.

“Everything,” was all Randy said. And right then I didn’t think he was crazy anymore.

We got married shortly after I turned twenty-two, having started dating from the summer before I entered high school with only a brief year apart when I went off to college. Yes, we started a band together, one we still play in occasionally. We never made it big, but we earned enough of a living to support three children of our own. Going from preppy girl to metalhead wasn’t easy, and it wasn’t always fun, but it was worth it. We destroyed the music and notes for “Song of Life,” the real version, and even convinced ourselves we forgot how to play it, but speaking for myself, the temptation to play it was always there, still is, and I don’t think it will ever go away. Some songs weren’t meant to be played by us, only by the one who wrote them, who wrote music into the DNA of humanity, in the first place. Because the older I get, the more I think music doesn’t originate in our minds, but gets whispered to us by something, or someone, outside of us. And when the time is right, Randy and I will be there, playing the solo that comes in near the end of ‘Song of Life,’ except it’ll be the guy named Randy holding the soloist, and it’ll be a chick with a guitar instead, playing the triumphal return of everybody who’d ever lived, Randy’s dad included.

- Alexander

Thank you for reading this short story. If you would like to read more of my fiction, please check out my books on Amazon. You can also throw a few coins into the tip jar at Buy Me A Coffee. Thank you, and God bless.

A wonderful story, thank you for sharing it. I especially liked that after the death of the song the next paragraph began with marriage.

From slice-of-life to paranormal scares to happy triumph! Masterful work, brother.