Temporal Investment

The first in what will be an informal series of posts touching on life in the pre-Internet age.

The Internet changed everything, some things for the better and some things for the worse. Music firmly falls into the latter camp. Popular music, at least. Rock music, in particular. But the industry as a whole suffered when the changing business realities of the Internet made it nearly impossible for artists to earn a living, and forever altered the attention spans of the music-buying public.

There are other problems, of course. Having an infinite array of music at your fingertips absolves one of the risk inherent in deciding which album to purchase. Therefore, music is less-valued, viewed more as a fungible commodity and less than a divine art form. The bean-counters and moneymen making musical decisions are another problem–with an ever-more fractured audience and mounting production and promotion costs, why take a financial risk on anything other than a sure-fire hit?

The below video, passed along by reader Hardwicke Benthow in the comments, explains things quite well in 20 succinct minutes. Notice the attention this video pays to the real, empirically verifiable decline in the actual musical quality of the stuff you hear today:

I’ll break it down for you in case you don’t have time to watch:

Historically, record companies would receive demo tapes from hopeful acts eager to make a career out of music. This, or having talent scouts go to clubs, was how labels found new acts.

The record company would throw some money at the newly-signed act to record and promote an album and tour or two to see if it caught on with the public.

If the new act caught on, great! If the new act didn’t, well, the record companies cast their nets wide enough the one or two acts who hit it big would financially lift the company, giving them the financial flexibility to go out and sign those new acts. In other words, the record companies were more willing to take risks because (a) it wasn’t cost prohibitive, and (b) they had the popular acts to buoy them on the balance sheet.

Some bands hit it big from album number one. Others took time to develop. The point is, labels actually took the time and didn’t immediately drop an underperforming act if it saw artistic and commercial potential.

At some point, though, even before the Internet came into being, risk-taking began to decline and artists all started to sound the same. Now, as with any money-making industry, there’s a certain level of imitation, with the success of Brand X being copied by Brands Y and Z and all the rest. This is unavoidable and not always bad, as competition can drive down prices and foster innovation and all of that.

But we’re talking about music. About art. The competition isn’t for a lower-priced album, is it? The competition is for better music.

Think about the so-called British Invasion of the 1960s spearheaded by the Beatles. Suddenly, a lot of shaggy-haired, smartly dressed British bands, many with Scouse accents, started popping up everywhere you looked, playing this exciting mix of amped-up, energetic American rhythm n’ blues and rock n’ roll. These bands weren’t all British, of course, but even American acts got caught up playing in this or similar styles. And you know what? They were good!

The Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Herman’s Hermits, the Dave Clark Five, The Kinks . . . there was a plethora of good music, and these groups pushed each other to be better. John Lennon thought The Kinks’ “See My Friends” was the most amazing song he’d ever heard and vowed to write better music to compete with it. The Stones and the Beatles had a friendly competition, and though slightly apocryphal, both the American Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds and Mothers of Invention’s Freak Out! albums floored Paul McCartney, who began working on a little record you might have heard of called Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

At some point, though, this started to change. I always liked how Frank Zappa put it in this interview:

Those old cigar-chomping guys who would take a chance on a weirdo like Frank Zappa, and his weirdo friends like Captain Beefheart, were replaced by younger A&R guys who thought they knew the pulse of the music scene better than the actual audience. We see here the beginnings of the record industry starting to shape tastes instead of catering to what the people actually want.

In any artform, there is and should be a certain level of vanguardism. But if you continually feed audiences stuff they don’t like or stuff that’s calculated to make a buck but not move music forward, you end up with a gray mass of similar sounding product that sounds like the money-making stuff which came before. Risk dries up, and the attitude of “I don’t know what the hell this is, but maybe the kids’ll like it!” is replaced with ”The kids’ll love this summer’s feel-good hit because it sounds just like last summer’s feel-good hit!”

And so we see technological progress as both a boon–Recording technology provides an infinite pallet for sonic imagination! Artists can cut out the middleman and get their work directly to the people! Listeners have all the music in the world at their fingertips!–and a curse–There’s no money in music anymore! No risk! Everything sounds the same because the big hits are written by the same two people!

But things change. That is the way of the world. “Changes aren’t permanent/but change is,” et cetera. Other forms of music have supplanted pop and rock. It’s not hyperbolic or inaccurate at all to say that rap has become the American popular music of the past thirty years. And as Rick Beato discussed in this video (which I discussed here), other forms of entertainment have likewise supplanted rock music.

This is neither objectively good nor objectively bad. It just is. However, subjectively, I am not a fan of these particular changes both self-inflicted (the music industry immolating creativity on the altar of money) and technologically induced.

I am talking, of course, about the death of the album.

* * *

As in many infuriating cases, Pitchfork.com’s talented and knowledgeable writers get so much right while getting so much wrong. Take their review of the recent 40th anniversary edition of Rush’s landmark 1981 album Moving Pictures.

Yes, the 1980s, starting with 1980’s Permanent Waves, showed the band eschewing lengthy, lyrically fanciful prog-epics in favor of more concise though no less complex songs with more personal introspective lyrics. Yes, the band’s “charming, gawky futurism” led them to experiment with cutting-edge technology and incorporate the sounds of contemporary music like reggae and new wave–there’s that idea of competition again! “When punk and New Wave came,” said Rush drummer and lyricist Neil Peart, “we were young enough to gently incorporate it into our music, rather than getting reactionary about it.”

Remember, by the time Moving Pictures was released, Peart was only 29 years old, and both bassist/vocalist Geddy Lee and guitarist Alex Lifeson were 28.

Naturally, Pitchfork has to bring race into it. Race, when discussing a band like Rush!

Someone in the Rush dressing room must have loved the Police who were, at the time, three albums into a career that would turn them into the world’s biggest band and most fractious trio. To absorb Black rhythms through the filter of another white trio works as insurance: It’s less fraught to get blamed for borrowing from people who look like you. Rush experimented with a slight skank on Permanent Waves’ “The Spirit of Radio,” which might explain why it became an actual hit in reggae-drenched England than in an America that went through the trouble of keeping Black disco-tinged acts off the air.

That “someone” was the entire band, as a cursory Internet search would reveal. And to claim that a band which openly admired blues and jazz musicians, who had a drummer who literally went to Africa to drum with actual Africans and incorporated actual African rhythms into his drum parts and solos, who was influenced by black rappers when devising the rap (yes, you read that right) to 1991’s “Roll the Bones,” had to “absorb Black rhythms through the filter of another white trio” is pure bullshit. Then again, reviewer Alfred Soto is a professional journalist with a severe left-wing bias, so a certain level of bullshit is unavoidable.

Also, while Soto accurately describes Lifeson’s delicious guitar part to “Red Barchetta,” the song is much more than “an ode to the Italian roadster.” Did he miss the song’s not-so-secret narrative of taking place in a future where the internal combustion engine had been made illegal?

He also bewilderingly calls 1978’s Hemispheres instrumental “La Villa Strangiato” “rather ponderous” when compared to Moving Pictures instrumental “YYZ,” and yet, there are passages like this:

As Rush matured into their Moving Pictures era, their instrumental flourishes matched their newfound plainspokeness. An inspiration for bucketloads of maudlin crap, the touring life didn’t affect a muse that had shown to this point little interest in the larger world. “Limelight” presents no complaints—advice not wisdom, remarks not pronouncements. Bands who envy Rush’s gilded cage “must get on with the fascination/The real relation, the underlying theme.” Before anyone can say, “Speak for yourselves, dorks,” the trio builds toward a break less impressive for how Lifeson outdoes David Gilmour in guitar dive-bombing than in Lee’s bass licks. That’s why they’re Rush and you’re not.

It’s maddening to read reviews on Pitchfork, but they nail it often enough for me to keep coming back.

But this isn’t about Pitchfork. This about why an album that’s as old as I am is still being talked about with such detail and scrutiny to this day.

* * *

Let me take you back to a different time, a time when the Internet existed, but it was not ubiquitous. A time when cell phones were massive by today’s standards and could be used for exactly one purpose (making phone calls). A time when people still purchased and enjoyed music the way it had been enjoyed since the ability to record and play back music.

That time was 1998.

That’s when I purchased Moving Pictures for the first time. I was a 17-year-old bass playing high school junior with long hair who had grown up on a steady diet of classic rock acts like Cream, Led Zeppelin, the Beatles, Jimi Hendrix, the Who, and Pink Floyd, in addition to grunge and alternative bands like Primus, Blur, Stone Temple Pilots, Nirvana, Smashing Pumpkins, and . . . uh . . . the Red Hot Chili Peppers (we all make mistakes).

Prog rock was a serious gap in my musical knowledge, Pink Floyd fandom aside, but after reading a retrospective review of Moving Pictures in the pages of Bass Player magazine (I could write an entire other post about how awesome magazines used to be), it piqued my interest enough to buy the album for myself.

I knew “Tom Sawyer” from the radio. I knew about the “REE-ner-REE-ner-REEEEE-nerrrrrr” keyboard part and Geddy Lee’s high-pitched, androgynous voice. My dad, never a fan, used to crack up when it came on the radio, so I never actually heard the song. But I do recall hearing “Limelight” on the radio one time waiting with my mom to pick up my sister from some after-school thing. We caught it mid-guitar solo and I was stunned by the emotional quality of Lifeson’s solo, the growl of Lee’s bass, and let me tell you I even liked the keyboards.

Back then, a new CD was somewhere in the $12-$15 dollar range. I think I found Moving Pictures at our town’s local music store (remember those?) at the lower end of that spectrum. I popped it in on my drive home and I was hooked. First chance, I got, I put the CD in my Discman (remember those?), took out the lyric sheet, and followed along until the album was complete. And then I think I played it again.

That’s how we listened to music in the pre-Internet days. It wasn’t specific to Rush, either. Any album you bought with your hard-earned money was listened to in this way. Or maybe you had an awesome stereo system you used instead of headphones. The important thing was that music did not become background to being on your phone or playing a video game. It was a thing you sat down and focused on exclusively. That is how you got inside the music.

Albums were important as they represented the total package. Why did the musician choose that artwork? What does the artwork say about the music? Why were the songs sequenced in this way? What message is the musician trying to convey?

I think about bands like Rush or Pink Floyd who had great artwork. Or about band photographs and posters that left indelible marks on your mind. Maybe we just valued it more, trucked ourselves into connecting with it, since we had to make choices in what music we wanted to purchase and what’d we’d get taped copies of from friends or from the radio.

Bemoaning the “death” of the album is overblown melodrama. Of course great albums are still made with the same attention and talent and care. It’s just that they seem–and again, this is one man’s perception–they seem not to matter as much to as many people.

Moving Pictures became my album. I learned those seven songs note for note, word for word, from the loudest cymbal smash to the tiniest pick scrape. I fell into it and it became important to me in a way that all good art does. Fitting with the album title, it moved me, eliciting emotions that resonated far after I took my headphones off and moved on to doing something else.

“Tom Sawyer”? Boundless freedom and optimism. “Red Barchetta”? The thrill of committing infractions against unjust laws and simply enjoying life. Pure exhilaration. “YYZ”? Busy travel resolving in the comforts of home. “Limelight”? Alienation. The bittersweet realization that fame is not the happy thing sold to us. “The Camera Eye”? You feel the pulse of the city, the quality of any large spaces human beings gather, how we overlook these things, take them for granted, and sometimes need to focus on a snapshot to capture those feelings. “Witch Hunt”? The dangers of demagoguery. Emotions turned into weapons. “Vital Signs”? The importance of communication to truly being human. Man as machine, but so much more.

Certain albums became a part of your life, and in a weird way of your identity in a very visceral, internal way. Music made you think about more than just the music. It opened doors into your own creativity and how you perceive the world, provided you imbibe the music in the proper manner. This is why you must be just as careful about how you feed your head as what you feed it.

* * *

The album as an cohesive object appeals to a small niche that is not age-specific at all. I am not trying to be the proverbial old man yelling at a cloud here. Instead, I’d like to expand that niche by encouraging people who came of age stepped in Internet culture to think about a few things the next time they decide to put on some music:

Buy some music on physical media. I recommend an album, but the choice ultimately is yours.

Set aside some time, even if it’s just ten minutes, to do nothing but listen to your music of choice. No phone. No computer. No gaming. No distractions. Pick a song or three, or maybe an album, and focus on that.

If the album has a lyric sheet, follow along. If it doesn’t, and you trust yourself enough not to surf on the Internet while listening, find the lyrics online and follow along like that.

Close your eyes. Pick an instrument, or the vocals, and follow that. Listen to the subtleties. The next time you listen to that song, or maybe even on the next song, focus on something different. If you can, focus on the interplay of sounds and timbres.

If you find your mind start to wander and you’re not focusing on the music, that’s a good indication that it might be time to take a break. Or, restart the song.

You’re not going to memorize a song or an album after one listen. I’d say it takes at least 10 for it to really stick with you. But that’s the thing about this approach: it imposes artificial constraints on the amount of music you are able to consume. The endless Spotify playlists are fantastic, of course, but I encourage you to put yourself in the shoes of someone with no Internet, limited funds, and a handful of albums to really get to know. You will have the patience to listen to a slowly developing song all the way through to get to the hook, the catharsis, because you have to.

Delayed gratification is a secret to winning at both life and music.

This is why albums mattered so much to people in the pre-Internet days. It’s like how members of ancient civilizations memorized entire books’-worth of knowledge and legend. There was nothing else to do, and that was a beautiful thing.

In my opinion, the worst thing about modernity is not the overabundance of leisure time, but the overabundance of what we are given to fill it with. Endless, streaming, algorithmically curated entertainment designed to get you to zone out and consume without thinking.

Screw that. It’s time to be deliberate about what you consume. And despite the music industry’s sad state of affairs, I find music to be a great place to start. Much like a book, listening to music the right way–and there is a right way–demands a temporal commitment. It demands your time and your energy. It demands something out of you. To truly get music is to be active. Let the Marvel movies be your passive entertainment, if you must. Let music be something special.

I firmly believe that if you try this, you’ll understand why albums and music in general mattered so much to those of us who grew up without the flattening effects that the Internet had on music.

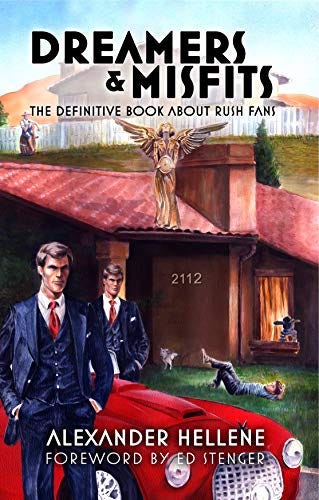

– Alexander