Planes, Trains and Automobiles (1987)

“Movies, more than anything else, offer up a true time capsule of days gone by . . .”

Given that the next story is taking a while to finish, here’s an essay I wrote last Thanksgiving about one of my favorite movies, but never published. Hope you enjoy the placeholder before the next story drops.

Movies, more than anything else, offer up a true time capsule of days gone by. I don’t mean historical dramas or period pieces, but movies set at the time and in the cultural milieu of when they were made, because they try to capture and reflect the now. Not only are movies one of the more popular forms of entertainment, but the fact is things you can see just feel real, even if the people and events depicted are fake. Most people’s knowledge of the Wild West and World War II, for example, come from movies written by people who weren’t there. Yesterday’s fiction becomes historical fact.

But beyond period pieces, the behavior of film characters has a profound effect on the behavior of people, usually young ones but also adults. When American Pie came out, I noticed the behavior of my peers change. Characters on screen acted a certain way, after all, so it must be okay. Normal, even. If you think this makes most people easily manipulated sheep, you’re right. You are too. So am I. This is why it’s important to make sure people are getting the right messages, and “right” depends on who is in charge and what their morality is. More than laws, arts and entertainment instruct and shape behavior. Religion used to do this—through art and stories and song—but religion, at least Christianity, hasn’t really mattered in America for nigh on a century. In the absence of any meaningful high culture, pop culture is all we’ve got. So all you aspiring politicians and policy dorks, forget it: if you really want to change the world, go into entertainment.

So what happens when someone who is, dare we say, traditional, gets a chance to make movies? What then? Does his work serve to change people’s minds, their behavior? In the case of John Hughes, no, but his art is really good and emotionally resonant, and has stood the test of time. Despite the occasional forays into absurdity, Hughes’s movies feel real.

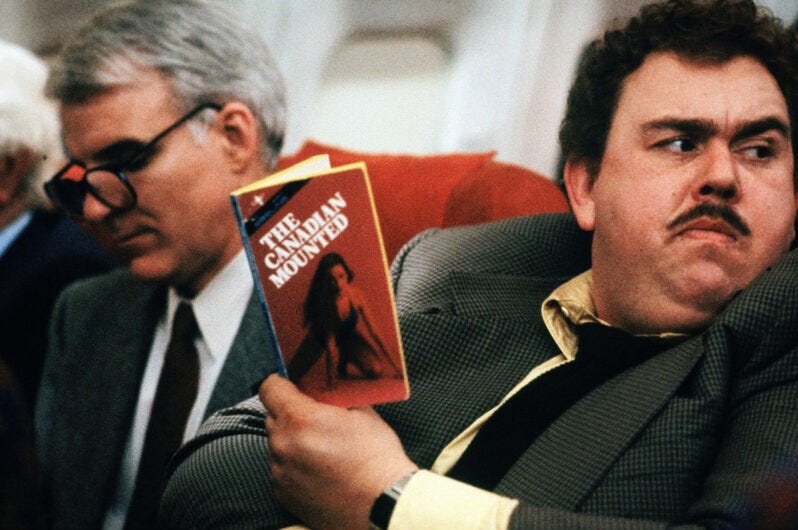

It was Thanksgiving recently here in the U.S., which means it was time to watch what is the best, and likely only, Thanksgiving move, 1987’s Planes, Trains & Automobiles. PT&A is a true two-hander, featuring Steve Martin and John Candy playing off each other beautifully.

Martin’s Neil Page is a high-powered marketer trying to get back home from New York City to Chicago in time for Thanksgiving two days prior to the holiday, one of the busiest travel days in America. He is high-strung and irritable, a combination few actors can play as believable—and hilariously—as Martin.

The late John Candy portrays traveling shower curtain ring salesman Del Griffith, a honest, genuine, and sincerely good man—albeit a highly annoying one—in a similar predicament as Page. They meet when Page, trying to hail a cab to LaGuardia to catch the 6:00 flight to O’Hare, is continually thwarted by competing businessmen, including a young Kevin Bacon and a real asshole of an attorney (when asked by Page, shelling out $50 bucks to get the cab, if he has any decency, the attorney says, “No, I’m an attorney.” In art, truth.). Finally securing the cab, a third person swoops in and takes it, prompting Page to run after and open the door. Inside, of course, is Griffith.

Stymied, Page gets to the airport late, but his flight is delayed due to a snowstorm in Chicago. Whew! Sitting at the gate, who is across from Page except for the cab-stealing Griffith. Thus begins their misadventure, the two men fatefully linked to keep crossing paths. For a reason? Maybe.

Page and Griffith get rerouted to Wichita, Kansas. After surviving a night together at a cheap motel (where they get burgled of all their money at night),1 they hitch a ride in the back of the proprietor’s son’s pickup to the fictional Stubbville, where they catch a train, albeit riding in separate cars. The train breaks down, of course, in Jefferson City. They’re able to ride a bus to St. Louis, with more trouble traversing the final 296 miles to Chicago. They part at a restaurant, and Neil rents a car . . . which isn’t in its assigned spot.

This has happened to me before, and while I had no trouble getting a replacement, it’s sad to see incompetence in the service industry was a feature back in 1987. Or maybe it was a bug, and the comedy came from the audience thinking things would never be this ridiculously bad. While still funny today, it hits differently.

Somehow, Del finds a rental car where and also runs into Neil, almost literally, setting up one of the funniest parts of the movie, followed by its most poignant. Anyway, halfway there they’re forced to ride in the back of a milk truck to the Windy City.

We’re not going to recap the movie scene-by-scene, but there are certain aspects that jump out that touch how different the America of 1987 was from the America of 2024 going on 2025. It’s easy to think that not much has changed, fashion aside—1987 was basically now without internet and cell phones, right?—an understandable assumption given our cultural stagnation these past four decades.

But this movie, like all by Hughes, evokes the feelings of the era so closely it hurts. I am roughly Hughes-favorite Macaulay Culkin’s age, and if you were that age during the 1980s you will know what I mean. Hughes captured what the era was like, but with an idealized childlike whimsy, even in a movie like PT&A, that straddles the line between schmaltz and sincerity.

And sincerity is the name of the game. Despite being occasionally crude and surrealistically absurd, PT&A never loses sight of the core assumptions underlying traditional America: Family is important, important enough to do anything to be with. Holidays like Thanksgiving matter because they speak to us as a people, and we want to participate. The bond between husband and wife is powerful and mysterious. And that it is always, always, good to have friends. (And male friendships, at that, which don’t have to be full of latent homoeroticism, “Why are you kissing my ear?” aside).

There is no irony poisoning or nihilistic posturing in PT&A. The annoyances, some petty some gargantuan, of travel are played for relatable laughs because, hey, we’ve all been there. Even when Page is chewing out the Marathon car rental lady or the taxi stand guy, he doesn’t get away with being a mean asshole—there are consequences even though we totally understand his frustrations boiling over.

And then there’s Griffith, well-meaning but with the social grace and awareness of a walrus. He is of a different class than Page, displaying a proletariat tackiness in contrast to Page’s bourgeois refinement. Griffith is a straight shooter who says what’s on his mind and is willing to make amends for inconveniencing a complete stranger, even if his remedies create more problems. Griffith is fat, wears loud clothing, smokes cigarettes and drinks beer, flies coach, stays in shoddy motels.

Notice how Griffith always “knows a guy.” He sold the Braidwood Inn some shower curtains a while back, so they’re able to get a room. Griffith even knows Doobie the cabbie who takes them there. He’s got a buddy at the train station, and another at a car rental place. The life of a traveling salesman has its perks, as does willing to genuinely interact with the lower socio-economic classes dotting the American heartland. These are not bad people, just ignored, but despite some ridiculous exaggerations, Hughes always treats his subjects with affection and respect.

A midwesterner, as well as a conservative Christian, Hughes has no heart for coastal condescension. His movies take place in exotic locations like suburban Illinois; far from being a bland hellscape of conformity, racism, misogyny, and repressed desires, the suburbs of John Hughes movies represent stability, decency, normalcy.

And you know what? 1980s America was like that. It was, by and large, a great place to grow up in and live. Not for everybody, you pedant, sure. Not everywhere, smart guy, are you happy? But by and large, on average, it feels like a relative paradise.2 Movies like this drive the bittersweet point home.

You will laugh at Planes, Trains & Automobiles, but if you were alive back then you will also cry, just a little bit, at the world depicted which is never coming back.

- Alexander

I hope you enjoyed this review. If you would like to read some of my fiction, please check out my books on Amazon. You can also throw a few coins into the tip jar at Buy Me A Coffee. Thank you, and God bless.

There’s a deleted scene which, when viewed, explains both the burglar’s identity and motivation.

I mean, no internet! No smartphones! Sign me up.

People have started to view video games as time capsules now, too. A certain youtuber went into how GTA4 was a product of the mid 2000s and damn it, it sure was. I digress.

I watched this movie a few years ago during COVID and it made me long for the 90s and early 00s when things weren’t nearly as bad.

There was no one like John Hughes or John Candy. Both gone much too soon.