The Name of the Rose, Umberto Eco (1980/1983)

“Historical fiction is a tricky beast. Rare is the modern writer . . . who can resist having characters ostensibly living in ages past parroting the author’s own personal modern beliefs . . .”

Historical fiction is a tricky beast. Rare is the modern writer—that is, of the 20th century and later—who can resist having characters ostensibly living in ages past parroting the author’s own personal modern beliefs. Or making predictions or statements that predict Current Year—it’s not cute, it’s not clever, it’s too on-the-nose, and it’s boring.

Umberto Eco’s The Name of The Rose is historical fiction done right despite some of the annoyances I listed being present. Yes, William of Baskerville is basically 1327 Umberto Eco, or at least a thoroughly Modern Man who shares many of Eco’s beliefs, in addition to being a rather obvious Sherlock Holmes expy.1 But Eco, an atheist as well as a talented writer, is able to make an early fourteenth-century Franciscan monk mostly think and act and believe like an early fourteenth-century Franciscan monk. No “doubt is the sincerest form of faith” or “the religious are stupid and benighted superstitious idiots” here. William might be hip to the latest in philosophical and scientific developments, but he uses them to discover the truth in God’s creation, not to try and disprove his own religion.

Not only that, but The Name of the Rose is so compelling, so well-written, so alive, that the ending didn’t annoy me nearly as much as it would have in the hands of a lesser author.

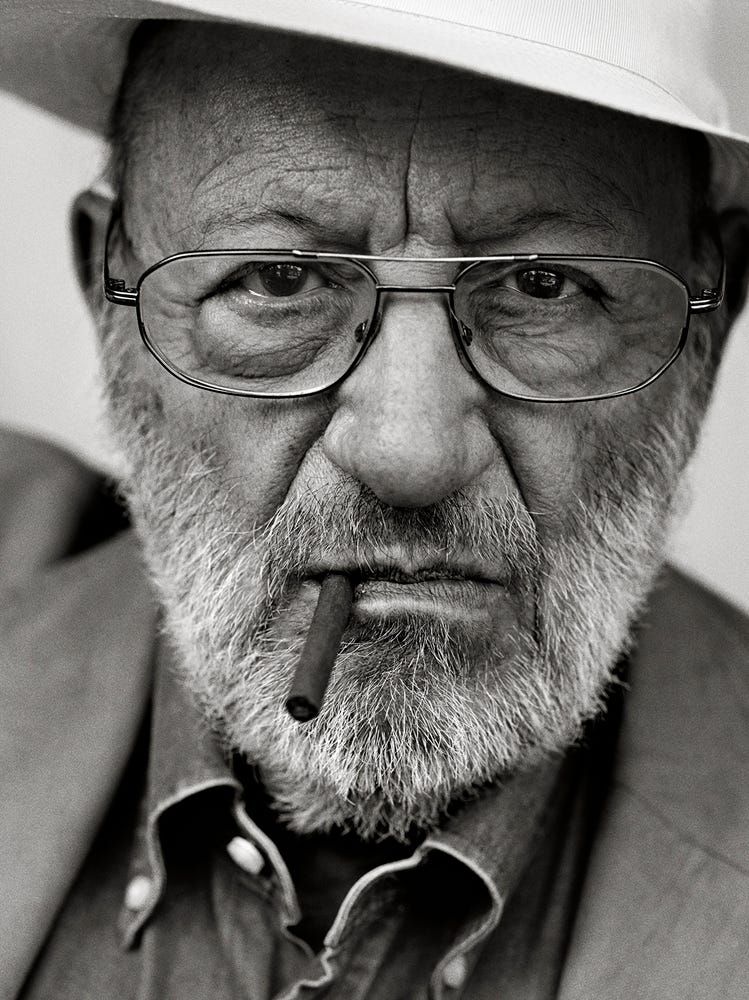

Umberto Eco (1932-2016) was an Italian philosopher, critic, semiotician, and medievalist who decided to get into the fiction game. The Name of the Rose, his debut novel, was first published in Italian in 1980 and translated into English in 1983. Drawing on Eco’s scholarship on both medieval Europe and the nature of signs and symbols, The Name of the Rose is a murder mystery set in late 1327 in a nameless Benedictine abbey atop an Italian mountain. The English Franciscan monk and former imperial inquisitor William of Baskerville arrives with his assistant, the young Adso of Melk, primarily to help represent the Franciscan view about the poverty of Jesus against that of Pope John XXII, with the Benedictine abbey being used as a neutral venue for the debate. This was an actual theological issue in the Catholic Church, and Eco peppers The Name of the Rose with some real historical figured, including the inquisitor Bernard Gui, the Franciscan Michael of Cesena, and the cardinals Bertrand del Poggetto and Jerome of Kaffa. There’s also the matter of Pope John XXII’s tensions with the Holy Roman Emperor Louis IV. So a lot is going on, and Eco thrusts us right into this milieu.

When we begin, William and Adso, through whose memories as an old man the story is told, are marching up the mountain pathway leading to the abbey. We immediately see William deploying his considerable intellect to deduce that one of the abbey’s finest horses has escaped, and the attendants are looking for him. William even correctly deduces the horse’s name. This ability, honed through studying the works of Roger Bacon and William’s friendship with William of Occam (of razor fame), will come in handy as Abo the abbot needs William to figure out what happened to one of the brothers, Adelmar. Adelmar’s body was found on the cliffs below. Did he jump? Or was he pushed?

And so our murder mystery begins. The Name of the Rose straddles the line between cozy and intense, because while you get a lot of the interesting historical stuff and sparkling, philosophical and theological conversations between William and Adso, and the two of them with the other monks and personages who come to the abbey, you also get some grisly murders as other brothers are picked off one by one. Is this the work of a serial killer? But who? In a closed environment like this, everyone is a suspect.

Venantius the translator . . . Malachi the librarian . . . Berengar the librarian’s assistant . . . Remigio the cellerar . . . Severinus the herbalist . . . old blind Jorge. . . Nicholas the glazier . . . Alinardo the eldest monk . . . bitter old Aymaro . . . Benno who seeks knowledge . . . monstrous, crazy Salvatore . . . some have scandalous pasts, some have hidden appetites, but do some also have reason to murder?

It makes for a compelling story, coupled with Adso’s own maturation in spirit and intellect, and a few other, more prurient ways. Still, Eco doesn’t revel in nastiness. All of the monks, William included, take Christianity very seriously. In Gen X or Millennial hands, he’d be a snide and snotty know-it-all, probably a secret atheist who is somehow more Christian than all the dumb believing monks. But Eco was a special writer.2 His William might disagree, might have strange opinions of his own which are a tad anachronistic, but he is never a hectoring, judgmental, obnoxious bore.

And then there’s the matter of the papal legation, which further complicates the investigation.

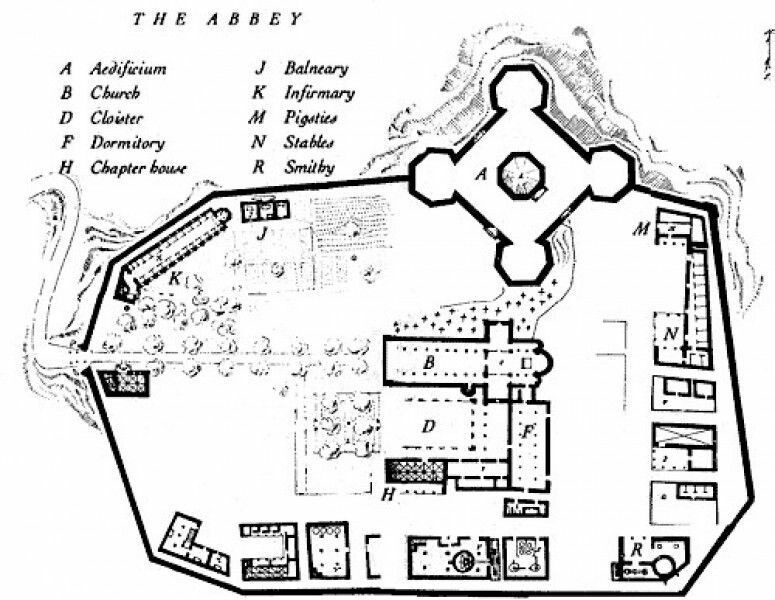

The abbey itself becomes a character. It is dominated by the Aedificium, a giant, four-towered fortress housing the kitchens and refectory on the first floor, the scriptorium on the second, and on the third, prohibited to all but the librarian, the great labyrinthian library. Which, of course, William and Adso must venture into to solve this mystery. What is the secret of the finis Africae? What is the secret of the abbey that someone is willing to kill for?

I do not want to spoil anything about this book for I want all of you to read it as blind as I did. Just have a website ready to translate all the Latin used by the brothers.

Eco was a medieval scholar, so his knowledge of the times gives The Name of the Rose a richness that will transport you. He was also a semiotician, so the story is also rife with symbolism. The reader must assume everything that happens, everything that is said, is there for a reason, and has meanings beyond the surface. Without saying any more, this makes the ending more thought-provoking, and while I’ve read the ending called “post-modern” both as critique and praise, I find it somewhere in between. At the very least, you will be thinking about it long after turning the final page.

I have little to criticize in The Name of the Rose. As mentioned, William sometimes becomes the stereotypical “Modern man in the ancient world,” which is good for a few eye rolls, but is a mild irritation and not enough to ruin the book. On the whole, he is likable. Likewise, Bernard Gui is a little too on-the-nose as a superstitious and power-mad heretic-hunter. Likewise, all the Papal delegate come across as cartoonishly corrupt, which might be Eco’s own biases coming through. Or maybe they really were that corrupt.

Further, this is an overstuffed, maximalist book, that some might find overwritten. Me, I love these flights of fancy, the ruminations on a carved door or a certain hymn, the philosophical and theological debates, or the vivid detail of Adso’s dreams and visions. Other readers might not, so consider that before picking it up.

But the good far outweighs the bad. I know I’m late to the party, but I’m glad I read this book. If you haven’t, you should. The Name of the Rose gets my highest recommendation.

- Alexander

Thank you for reading this review. If you would like to read some of my fiction, please check out my books on Amazon. You can also throw a few drachmas into the tip jar at Buy Me A Coffee. Thank you, and God bless.

“An expy (short for "exported character") is a character from one series who is unambiguously and deliberately based on a character in another, older series. A few minor traits, such as age or hair color, may change, but there's no doubt that they are almost one and the same.” TVTropes.org, “Expy,” available at https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/Expy#:~:text=An%20expy%20(short%20for%20%22exported,almost%20one%20and%20the%20same.

Eco, in fact, avoids many an annoying trope, and plays with reader expectations, and even when he does employ them a well-worn trope, he does it masterfully.

Excellent book! I agree, William of Baskerville has a few moments that veer a bit too close to modern sensibilities, but overall Eco pulls it off admirably.

My favorite Umberto Eco novel is "Foucault's Pendulum."

Thank you. I’ve added it to my wish list!