The two certainties in life are death and taxes,1 and aging is just the process of death. The funny thing about getting old is that you change. You mutate. You evolve.

At least, your brain does. And maybe, hopefully, your soul does too.

A surefire way to recognize the impact of change comes when you interact with art that resonates with you when you were younger. Does it hit the same way today? Does it hit differently? Does it bounce right off you now?

I watched Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back when it came out in 2001. I thought it was the funniest movie I’d ever seen. I was not quite 20.2 A few years later I watched again and was appalled by how unfunny and downright disgusting it was. People change, and the process of aging (i.e., slowly dying) should never be greeted with fear or dread, but just acceptance.

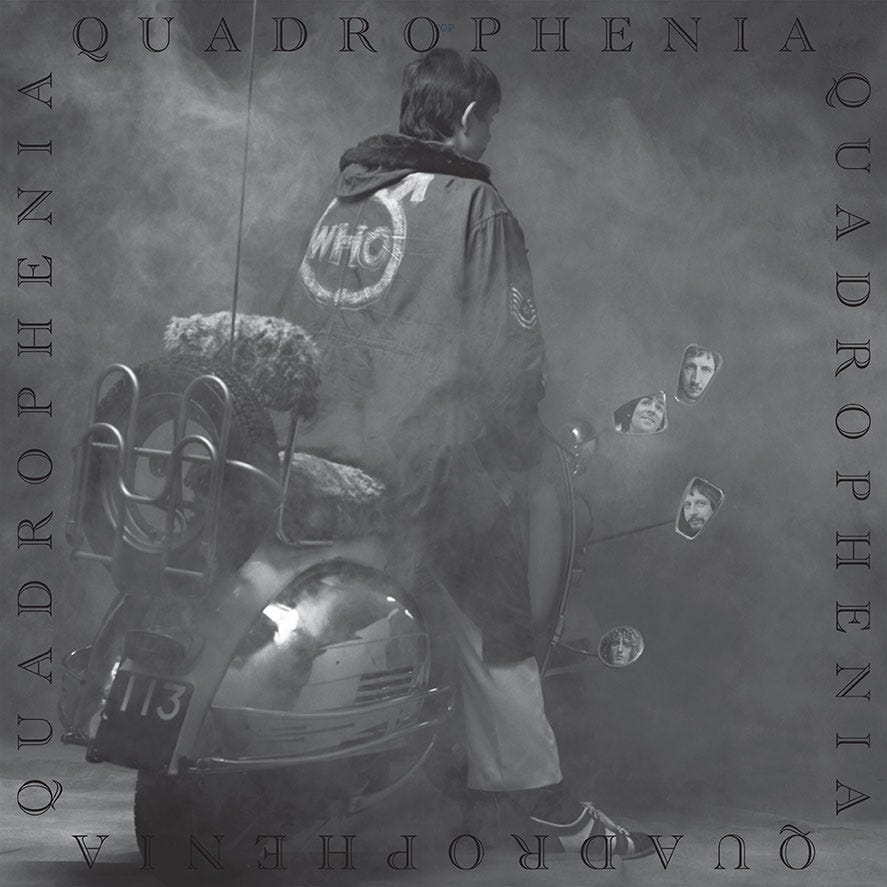

This acceptance settled on me like a fine cloak when I recently listened to an album that was a favorite of mine when I was a teenager: the Who’s Quadrophenia.

The Who were (are?) a fine band, one of my favorites. Pete Townshend knew how to write a hook, and all four members played with an energy that makes it hard to sit still while listening. And yet, they had a lot of subtlety and compositional acumen lurking beneath the proto-punk vigor. A great sense of humor, too. In fact, my biggest knock on the Who is that they didn’t rock enough; for every banger there were two or three softer or more contemplative numbers. And these are good! It’s just, you know, they were so good at the CRASH BANG BOOM stuff I wish they did more of it.

They also smashed their stuff after concerts,3 for a time anyway. Despite this habit for violence and destruction, Pete Townshend was ultimately too smart for rock and roll. Ah well.

So Quadrophenia. The band’s second rock opera and second full-length studio album after their first rock opera Tommy (1969) and their first aborted rock opera Lifehouse, bits of which were salvaged and fashioned into what many consider the band’s best album, Who’s Next (1971).

Quadrophenia4 tells the story of a teenaged boy named Jimmy trying to find out who he really is. He has, ahem, four personalities, each one represented conceptually by a member of the Who and musically by each member’s theme: “Helpless Dancer” (vocalist Roger Daltrey), “Bellboy” (drummer Keith Moon), “Doctor Jimmy” (bassist John Entwistle) and “Love Reign O’er Me” (guitarist Pete Townshend). It sure means something, let me tell you.

Jimmy lives in a specific place (England) in a specific time (late 1950s/early 1960s) during the heyday of two very specific, very English subcultures (the Mods and the Rockers) and the war between them. Jimmy is a Mod (like the Who!) and beats up Rockers (like the Who?), but doesn’t feel like he fits in with the Mods. Or the girl(s) he likes. Or his family. Or the world, really.

So he does things. I don’t quite remember the story but I think Jimmy is trying on different personas to see what fits, but many of these are driven by what he thinks he needs to do to fit in. It’s very adolescent and I’m sure we can all relate. I sure did when I was a teenager. This album was on constant rotation, and the first real rock concert I ever went to was The Who playing the entirety of Quadrophenia back in 1997.5 It helped that it also rocked . . .

. . . in relative terms. Many tracks are full-force Who classics, like the ones everyone knows (the horn-led “5:15,” the bass-and-drums workout “The Real Me,” and emotional closer “Love Reign O’er Me,” which roars like the ocean Jimmy finds himself in the midst of at the story’s end), as well as some lesser-known cuts (“The Punk and the Godfather,” which the Who are in; “Drowned,” “Had Enough”). But the proceedings are so much more overblown6 than I remember. The band had always been bombastic, like their frenemies Led Zeppelin, but Quadrophenia is more than bombastic. It’s . . . dare I say it, a teeny bit cheesy. It’s like a musical, my least-favorite artistic medium: Roger really oversings everything, the arrangements are stuffed to bursting with horns and strings and pianos and synthesizers,7 and the lyrics are very on the nose, “THIS IS WHAT I’M FEELING RIGHT NOW!” fare (quite adolescent). It still works, mainly because the band was so talented and Townshend is such a brilliant songwriter.

I don’t use the term “brilliant” lightly. Townshend had a special talent. He uses complex chords, has a knack for structure and flow and shifting moods to heighten the lyrical impact, and his songs rarely overstay their welcome.8 He knows how to weave leitmotifs and musical themes into songs, sticking a variation of the “5:15” riff (in a different key!) into “Drowned,” interpolating the “My jacket’s gonna be cut slim and checked . . .” bit from “Had Enough” into “Sea and Sand,” interpolating the chorus of “Love, Reign O’er Me” into “Had Enough,” and writing two instrumentals that feature all four Who themes melding into each other. If you can get over the relatively one-note vibe of the album, it’s heady stuff.

But that’s the musical aspect. Lyrically, yeah, the songs don’t hit like they used to.

I’m not a teenager anymore. I’m not trying to impress girls. I’m old enough (42 this fall) not to care what other people think of me. I’m married with two children. I’m a dad, so I’m by definition uncool and I don’t give a shit. The world of Jimmy, of Mods and Rockers, of fashion and fitting in, of trying to impress girls by doing stupid things I think they care about, it’s like a different country to me, a different planet. Sure, I still sometimes have an existential crisis or three, but who doesn’t?

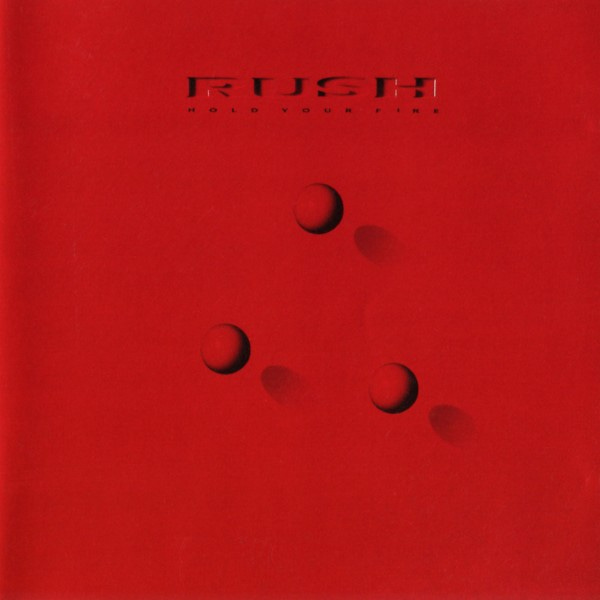

Being middle-aged has its own set of problems that different art speaks to. Hold Your Fire (1987) and Presto (1989) used to be my least favorite Rush albums (both made when the band members were in their late 30s). Now they’re two of my favorites.9 Blur’s new one, The Ballad of Darren (2023) strikes a similar chord despite not really “rocking,”10 and I think it’s great. I’m at the age where songs about loss, regret, and looming mortality mean more than songs about girls and partying. Who says getting older isn’t fun?

How old was Pete Townshend when he wrote Quadrophenia? He was 28. So an adult, maybe not by today’s standards but certainly by 1973’s. However, it’s obvious that, even as an adult, Mr. Townshend understood the teenage mind; the teenaged male mind to be specific.

While sometimes I find it hard to understand which character is talking about what, there are songs dealing with issues that all teenagers think about: disillusionment with the unfairness of the world and a desire to do something about it while adults just sit back and accept bad things as just “the way the world works”11 (“Helpless Dancer”); an adolescent’s gloriously childlike sense of right and wrong that is, more often than not, far less susceptible to sophistry and bullshit (but I repeat myself) than an adult’s (“Dirty Jobs”); learning that our heroes really aren’t all they’re cracked up to be (“The Punk and the Godfather,” “Bellboy”); first love (“Sea and Sand”); and the necessity of sometimes being alone in nature and having a good rage at the universe (“Love, Reign O’er Me”). Yeah, Pete got those awkward, difficult, wonderful, magical years between childhood and adulthood. It’s a shame that they don’t resonate like they used to, but the fault isn’t Pete’s. It’s mine. For growing up.12

Growing up happens to everyone. It just takes time. I look at my 30s and I’m embarrassed by how immature I acted in many situations, some public and some not. The problem with being an angry young man is that you become an angry adult, and that attitude takes some time to get channeled into productive avenues.13 Like many, I shared a proclivity for boundary-pushing and edginess that I chalked up to being artsy, but that too often bled over into something darker that I didn’t have the ability to confront until I got older. This is why a recent article about another music figure, guitarist, bandleader, producer, and all-around asshole Steve Albini really struck a chord (get it?).

Through the course of this article, Mr. Albini talks to a reporter from the Guardian (I know, I know) about a recent Twitter thread of his actually apologizing for some of the things he’s said over the years. Steve Albini! Apologizing! What will they think of next?

For those of you who don’t know, Steve Albini is a well-known abrasive prick who has made a career out of rubbing people the wrong way . . . and producing really cool music. While fronting the bands Big Black, Rapeman,14 and later Shellac, he also opened Electrical Audio studios, making albums for bands like the Pixies, Nirvana, and, if you can believe it, Page and Plant. Steve Albini was where you went to get instant cred.

He also said some questionable things that, regardless of your politics, are pretty offensive. He also eventually did that thing all straight white men in the entertainment industry do, which is apologizing for being a straight white male, which is pretty cringe, as if he got where he is at the expense of others! He can “make space” for others? Hey asshole, you already got yours, so of course you’re willing to “step aside.” What about the rest of us?

Anyway, this is an interesting perspective:

In 2001, the writer Michael Azerrad published Our Band Could Be Your Life, a history of the US independent music scene in the 1980s, which told the stories of bands like Sonic Youth, Fugazi and Big Black. What is striking, reading the book today, is not just how unrepentant Albini was about his past controversies – the appalling band names, the cruel insults, the jokes that toyed with racism, misogyny and homophobia – but how unbudging he was about why so many people had criticised him. To Albini, back then it was simple. Obviously he didn’t really believe in any of that stuff – if you read his interviews or thought about his music for two seconds, you would pick up on his real politics.

He had no time for people who are “careful not to say things that might offend certain people or do anything that might be misinterpreted”. That was just about seeming good rather than actually being good. “I have less respect for the man who bullies his girlfriend and calls her ‘Ms’ than a guy who treats women reasonably and respectfully and calls them ‘Yo! Bitch’” he told Azerrad. “The point of all this is to change the way you live your life, not the way you speak.” It did not seem to bother him that for people who don’t know your innermost thoughts and desires, the way you speak is the way you live; it doesn’t matter if you, personally, believe your politics are sound.

As the years wore on, his perspective started to shift. “I can’t defend any of it,” he told me. “It was all coming from a privileged position of someone who would never have to suffer any of the hatred that’s embodied in any of that language.” For years, Albini had always believed himself to have airtight artistic and political motivations behind his offensive music and public statements. But as he observed others in the scene who seemed to luxuriate in being crass and offensive, who seemed to really believe the stuff they were saying, he began to reconsider. “That was the beginning of a sort of awakening in me,” he said. “When you realise that the dumbest person in the argument is on your side, that means you’re on the wrong side.”

. . .

Now whenever any public figure is made to answer for their former bad self, they go on an apology tour where they say all the right things about being a work in progress, and learning and listening, and so on. Rarely do they break down the actual specifics of what they said, why it was wrong and why they regret it. But Albini, when I asked him about his public reassessment of his past sins, was pretty no nonsense. “I thought it was important to explain how some of the uglier and more confrontational aspects of my speech and behaviour came about,” he said.

It would be naive to claim that someone like Albini might serve as a “model” for how others might revisit their past failures. He didn’t have a tidy series of epiphanies fit for a TED talk; instead he slowly changed his mind over a long period of time. Still, it was instructive to hear him connect the dots about why he had felt entitled to talk the way he once did. “It’s exhilarating to feel like there’s this forbidden area that you’re not allowed to participate in, and when you go in it, you feel like you’ve discovered a tropical island: ‘They told me there was nothing here, and look, there’s something here,’” he said. “I understand that exhilaration.” But, he added, “I also know that we’re not as safe from historical evil as I believed we were when I was playing with evil imagery.”

In 1985, for instance, Big Black released a single called Il Duce, whose cover featured a stylised rendition of Benito Mussolini, and which was dedicated, in tongue-in-cheek fashion, to the Italian dictator. “We gave ourselves licence to play with this language because we felt no threat from it,” he told me. “We thought [the far right] was a historical anomaly, a joke for lonely losers. Even as the right wing became more openly fascist, we were still safe – and that’s where my sense of responsibility kicks in, like: ‘Oh yeah, I get it now. I was never going to be the one that they targeted.’”

You get older. You realize that being edgy for the sake of being edgy is actually pretty retarded (how’s that for edgy?). You want to yell rude words in polite company just to get a reaction. You want to say awful things to make prudes recoil in horror. You don’t really want to kill babies (do you?) but you can still admit that dead baby jokes15 are the height of comedy (just like Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back, I guess).

But eventually, the novelty wears off. Eventually, it starts to sting when people you actually like and respect don’t want to spend time with you anymore, quietly boiling off until you’re once again alone, the center of your own universe, the only star in your movie, which isn’t as fun as it used to be. Everyone else is moving on and you’re still in the same place you were when you were 30 . . . 25 . . . 23 . . . 18 . . .

That which seemed so burningly vital doesn’t matter so much. Other things take their place. Domestic things, boring things, things you used to sneer at but now provide you with great fulfillment, with meaning. You can still have fun, you can still enjoy yourself, but your interactions with that which used to fill your time is different. They’re not bad, they’re just not the same.

When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things.

1 Corinthians 13:11

Is it mellowing with old age? Getting soft, growing dull? All of your prickly edges sanded down into something more palatable? Are you—gasp!—conforming? Conforming to what? To whom? The corporate world which wants you to be a boring square, even as it pumped your head full of the entertainment you loved as a youngster, the stuff you found so important?

What the heck is going on?

I don’t know the technical term, but I can use a metaphor. Eventually, the trends and the scenes don’t matter because they’re not something you chose to devote your life to. They lured you in with the promise of camaraderie (real) and a sense of belonging (also real). However, the seductive aspect was the need to adopt a way of life that maybe you actually don’t like. Maybe you think the fashions are dumb, the lingo pathetic, the lifestyle choices lame.16 But they are signifiers of that belonging. A uniform. Conformity. And maybe you just got tired of the game because you really do want a wife and some kids who come running calling “Daddy, daddy!” when you get home from work and a home of your own away from the city and a little patch of land you can mow on the weekends. Maybe you do want to conform to the thing that the non-conformists conform to other stuff to get away from.

Maybe you cut the strings from the puppeteer you didn’t even know was above you. Maybe, and although this might not be the way Pete Townshend intended his lyric to be interpreted, maybe you stop dancing.

- Alexander

My brother posits a third: windpants on gym teachers. I think this is a worthy addition.

Yes, my friends, I must confess that—and may Christ forgive me for uttering these words—I used to find Kevin Smith movies funny.

Well, except for bassist John Entwistle, who typically just stood to the side while the destruction commenced.

There was also a movie from 1979 starring, among other people, Sting.

And it was glorious. John Entwistle was still alive, Roger Daltrey’s voice sounded great, Pete Townshend was still thrashing away on his axe, Zak Starkey (Ringo Starr’s son) killed it on drums, and Pete’s younger brother Simon held down rhythm guitar duties. They had a horn section, and noted kiddie diddler Gary Glitter played the part of the Godfather in “The Punk and the Godfather.” There were other guest stars I couldn’t remember. Some band called Drivin N Cryin opened and all I can remember is that their lead singer/guitarist had a voice like a girl’s. Not a high-pitched male voice like Robert Plant’s or Geddy Lee’s, but like an actual girl’s voice. Funny what you remember.

This is the best word I can think of.

To be fair, this is a continuation of Townshend’s masterful layering of acoustic guitars and pianos as a bedrock of pieces with the electric guitar adding extra flair over the top which he really got good at on Who’s Next, which in turn was a continuation of the arrangement style he started to develop in earnest on Tommy.

Even long ones like “Won’t Get Fooled Again” and “Who Are You” whiz by. Probably because The Who had the philosophy of “If we play everything as aggressively as humanly possible, it won’t get boring!” And that usually works.

Exactly one song on The Ballad of Darren could be considered “rock music”: the Bowie-esque “St. Charles Square.” “Barbaric” is less rock and more English new-wave. Very English: think The Smiths meet Modern English.

This attitude is one of several reasons I’ve moved so far away from modern American conservatism, because this acceptance (which is fine) is too often coupled with sneering contempt at people who “can’t make it” or “got a bad deal and lack the GRIT to pull themselves up by their bootstraps!” It’s prosperity-gospel nonsense that posits that people who can’t get rich deserve to suck because they suck and everything is their fault and that’s just how the world is and if you can’t become a smashing success the problem is you. As if getting rich is the only thing that matters in life.

Lest you think I’m writing off Quadrophenia in its entirety, I most certainly am not! It’s still an amazing piece of music, a towering achievement of ambitious rock and the Who actually pulled it off! When I was 15, I’d have rated it a seventy-gazillion out of 10, but now as someone entering middle-age, I’d give it a solid 8.

Like writing on Substack.

Sigh. Yeah. That was their name.

I remember an upperclassman who was way into punk couldn’t stop telling these in my 10th grade geometry class. He thought they were hilarious. They were not. He was also an upperclassman who had to take 10th grade geometry again, so make of this anecdote what you will.

Like drugs. I don’t care who or what you are or how cool you think you are, drugs are for losers and assholes.

My favorite Steve Albini story was how he mad he was when Urge Overkill jumped to the majors and all but said his incessant interfering is why their early stuff is garbage (and it is). IIRC he still holds a grudge against them to this day for that. But I don't think Albini could ever record an album as emotionally mature as Exit the Dragon anyway. (RIP Blackie)

Your talk about aging made me think of my own work, particularly Y Signal. I know some people said it could be considered young adult or read by kids, I think it works much better for older audiences. There is no way I would have been able to do something like that when I was younger, and I don't think I would have really hooked into it either. There is a way to write about youth and those juvenile days without being juvenile about it or clinging to the past. That's the sort of thing that resonates more with me.

Also, I agree with Kevin Smith's lack of maturity really not aging well. It would have worked had he had some sort of transformation in his own life that made him reassess where he came from and where he was going, but no: he still cries over corporate cape movies and deliberately tries to ruin childhood properties for people who like them. As a consequence, he has nothing to say and it makes going back to his early work really difficult when you have that context.

That isn't to say I don't like silly stuff. I do like a good bit of glam-style or deliberately juvenile music, but it's usually a bit more than mindlessly swearing and just trying to get under people's skin with nothing else to it.

That said, there is a reason when bands used to get older they would change their sound so much--like the Replacements or even Oasis did. You aren't the same hungry kid who picked up that guitar decades ago. Naturally, you're going to change, and it's up to you to make sure that's in a way that still connects with your base audience. I find that's what Albini and so many others miss. They didn't grow up so much as they grew away.

That reminds me years ago when I saw a random review of a then-recent Lamb of God album and the singer, who was just turning 40, I believe, bragged about how he was exactly the same as he was when he was 18 and hadn't changed in the slightest. All I could think of was how sad that was. Hopefully he has learned since then.

All that said, I can still find joy in an old Three Stooges or Tom & Jerry short, so there's that!

Not gonna lie: the Jay and Silent Bob movies still do it for me. Mallrats will (probably) always be one of my favorite comedies.